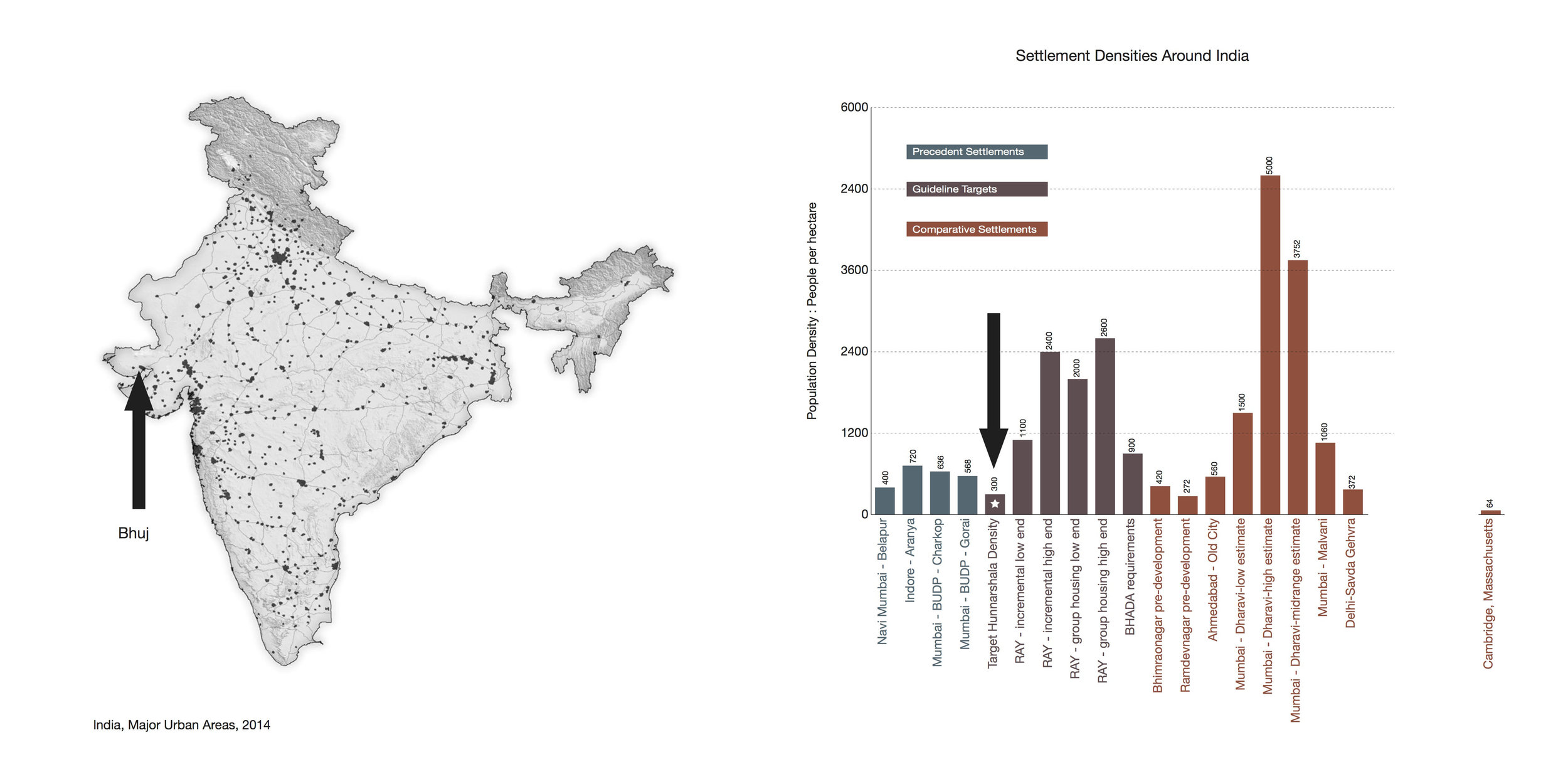

Bhuj is a small city of approximately 300,000 people in the Gujarat district of Kutch, in the far western part of the state. It is currently a pilot site of the Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) program of the Indian Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. The program “envisages a “’Slum Free India’ with inclusive and equitable cities in which every citizen has access to basic civic infrastructure and social amenities and decent shelter.” Locally known as the Slum Free Bhuj project, government and NGO organizations are working to redevelop the 74 existing slums in the city in the next five years, thereby improving the lives of the approximately 44,000 people living in them.

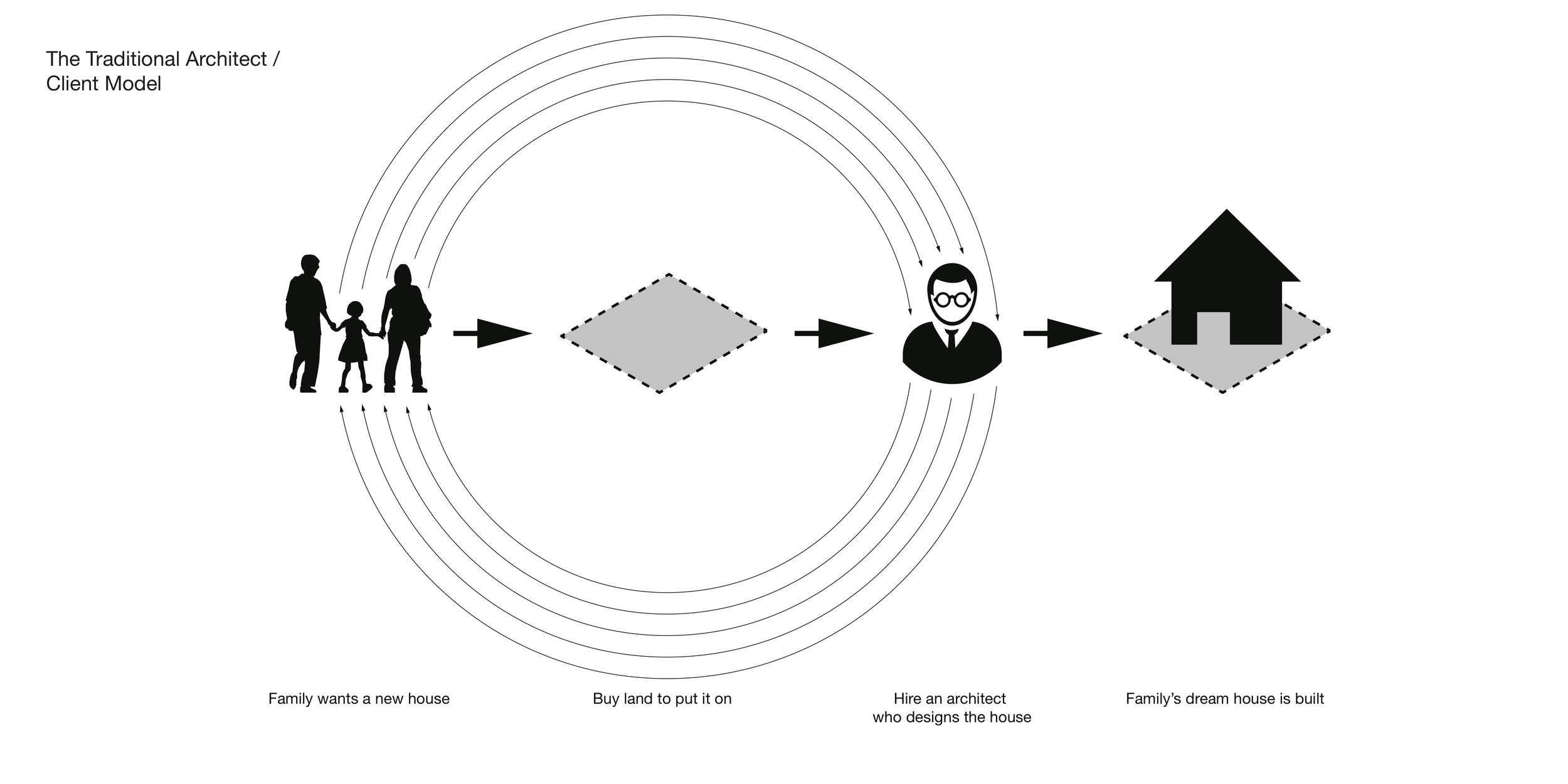

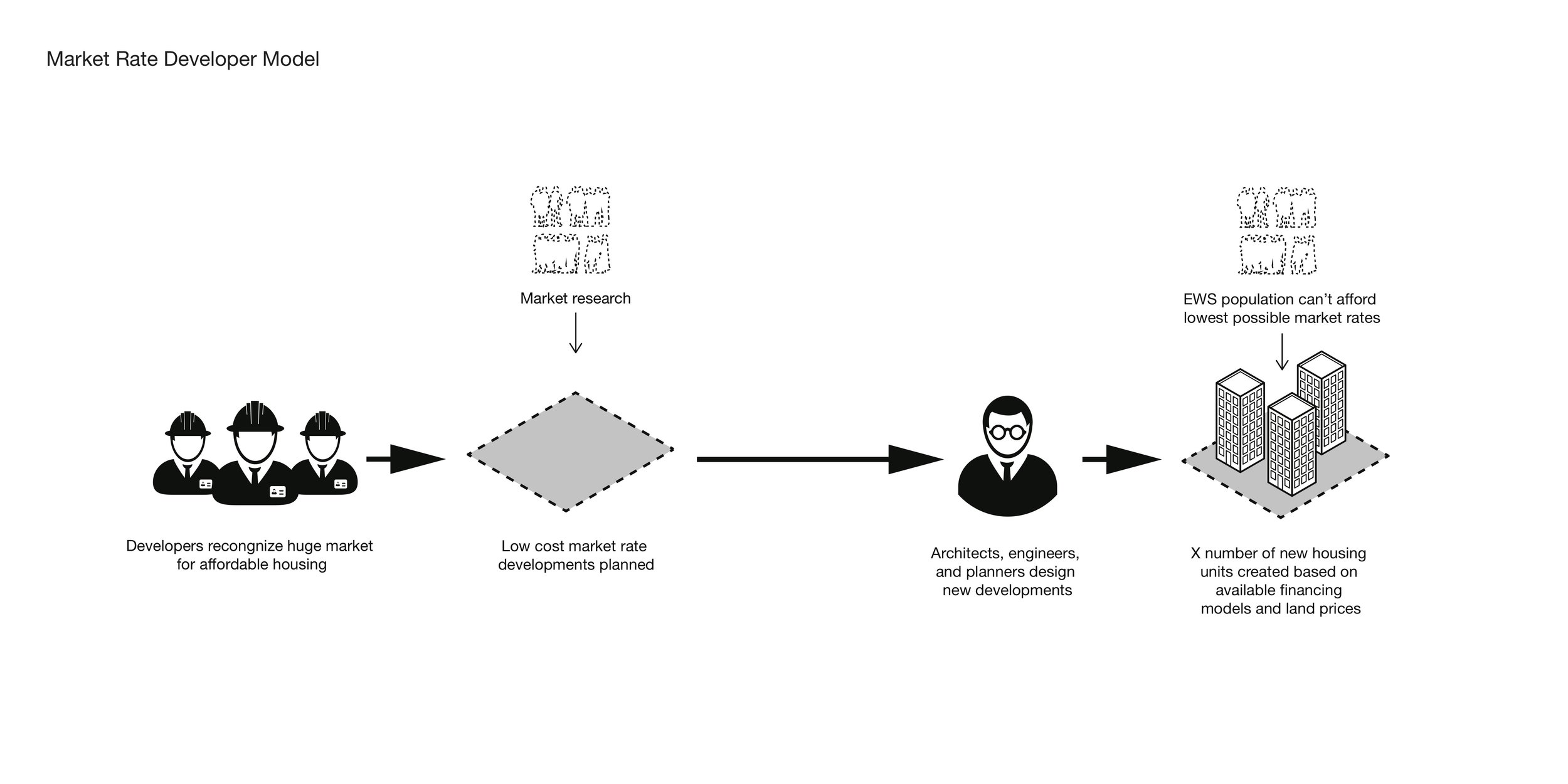

The development guidelines laid out in the official RAY process are extensive and quite laudable. Community surveys and active participation by community members are meant to be a key part of each slum redevelopment, allowing the slum dwellers to be integrated into the formal life of the city as full citizens with all the rights and responsibilities that implies. At its best, community participation in the redevelopment process would lead to community-specific design solutions for each redeveloped slum. However, given the scale of the project and the short time span it is meant to be implemented in, even a small city like Bhuj faces the threat of much easier to implement one-size-fits-all solutions all too common in cities around India, where banal, badly constructed concrete towers replace homes that slum dwellers have lived in, and in many cases thrived in, for years.

The central research question of this project is therefore this: can a community led design process be structured in such a way that it saves time while still allowing for the local specificity necessary to transform slums into neighborhoods fully integrated into the life of the city?

learning from the NGO, Hunnarshala Foundation, Formed soon after the Gujarat earthquake in 2001, this project aims to develop rapidly iterative design protocols for mass housing. The project makes use of design data and understanding of community interactions undertaken by Hunnarshala to build a step-by-step user participation methodology.

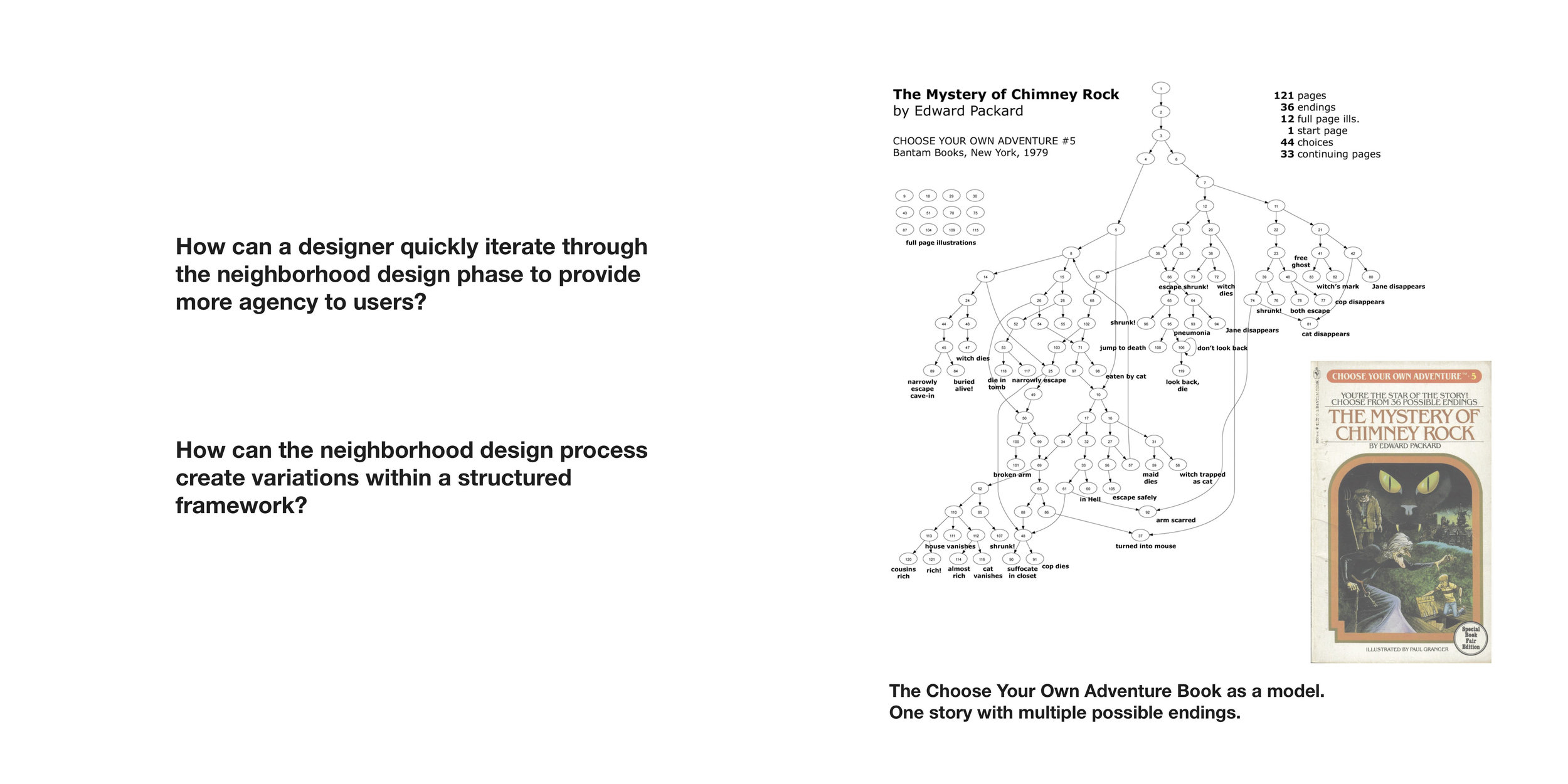

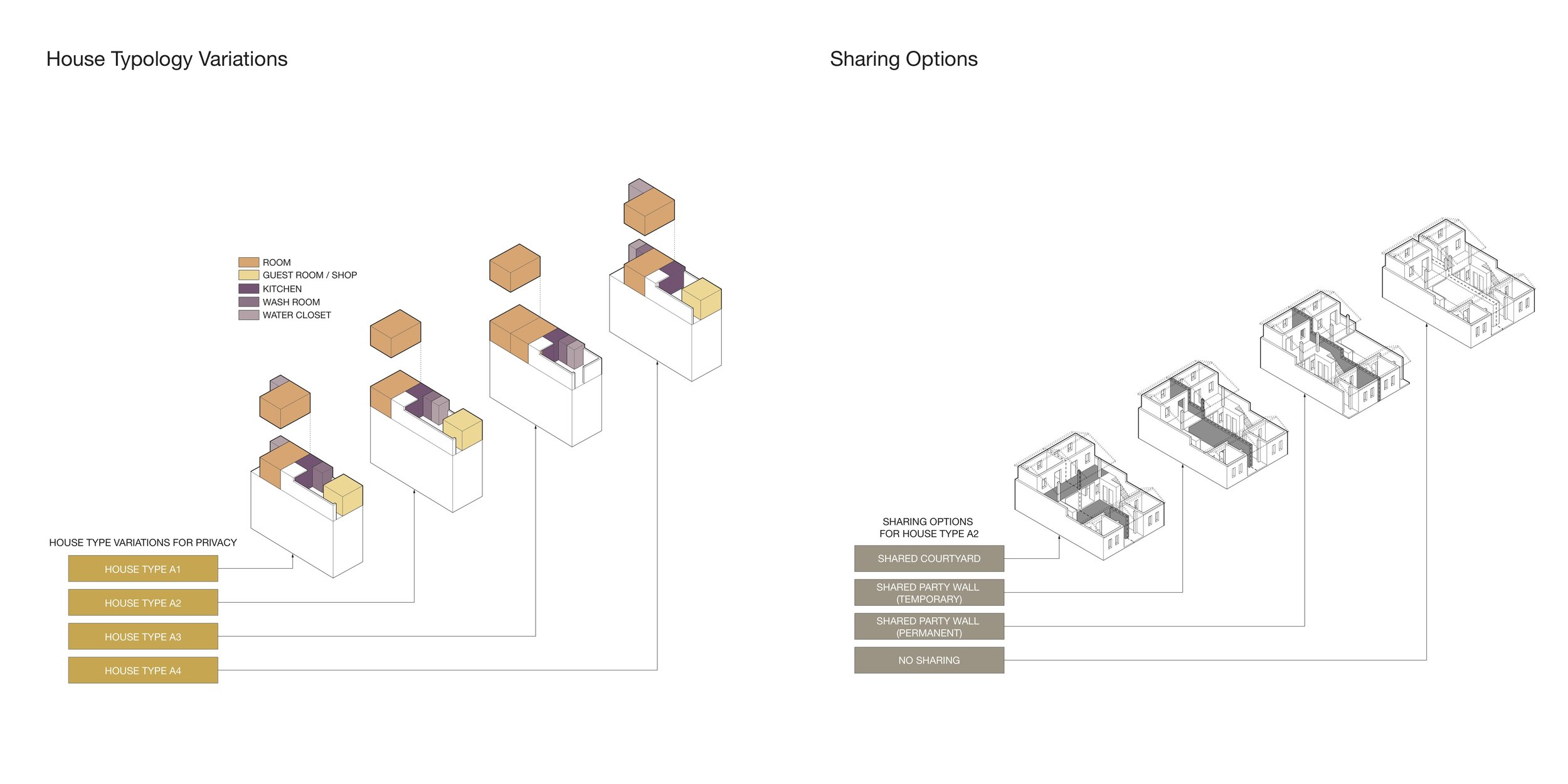

The logic of the participatory design guidelines are being developed in two ways. The first is for the community members. It is a guidebook that can lead toward a large number of possible outcomes, where many options are possible within a coherent framework allows for each outcome to meet a series of desired metrics. This decision-making process must be made in a coherent order with the appropriate group of people being empowered to make their own decisions at each appropriate scale. Currently the three scales being considered are at the scale of the entire community, the scale of the cluster or street, the scale of two families as neighbors, and finally the scale of the individual family itself. For example, while only one family would want decide where the water closet should go in their house, the entire community should have input on the settlement density, as well as if certain members of the slum will need to be relocated to achieve that density. By having an whole series of paths laid out in advance to allow for the multiple levels of decision making that need to occur in tandem in any community design process, this guidebook tool will allow for rapid design without sacrificing community specificity.

The second form the tools take is focused on the role of the design consultant. The decisions the guidebook addresses will be by necessity not based on individual sites. To bridge the space between a community’s formal decisions and way they formally manifest on a plot of land, the designer also requires a set of tools that allow for rapid iterations that respond to site constraints. Currently, design process for all the mass affordable housing is rather laborious, requiring slow, patient drafting that relies on copy-paste methods of existing prototypes that are resistant to the feedback loop of community participation or changing political climates, inevitably affecting projects as they are being developed. To increase the speed that the design consultant can manifest the design decisions of the community, a series of parametric design tools using common design software (Rhino3d and Grasshopper) are being created. These tools take the inputs of community decisions and rapidly allow site-specific outputs to feed the decision-making process.

Partners

Hunnarshala Foundation

Contributors

Urban Risk Lab: David Moses, Miho Mazereeuw, Aditya Barve

Hunnarshala Foundation: Sandeep Virmani, Tejas Kotak